It’s hard to deny that Frank Miller is one of the greatest comic book creators of the modern era. His work on Ronin, Sin City, and 300 is considered creative gold. There’s also his work on Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, which not only revived the franchise but also played a crucial role in establishing the “grim and gritty” anti-hero archetype that has since become a staple of modern superhero storytelling. However, before all of that, there was his run on Marvel’s Daredevil. This early work not only showcased Miller’s tremendous talent as both a writer and artist but is also widely credited with elevating the “Man Without Fear” from a relatively minor Marvel hero to one of the company’s most popular, profitable, and pivotal characters.

Videos by ComicBook.com

While Frank Miller’s work on Daredevil was undoubtedly foundational, nearly 45 years later, certain aspects of it — as a body of work — are less than perfect, have aged poorly, or simply do not measure up to current standards. However, to understand why Miller’s Daredevil run doesn’t fully hold today, it is crucial to first appreciate why it has been held in such high regard

Miller’s Daredevil was a Comic well Before its Time

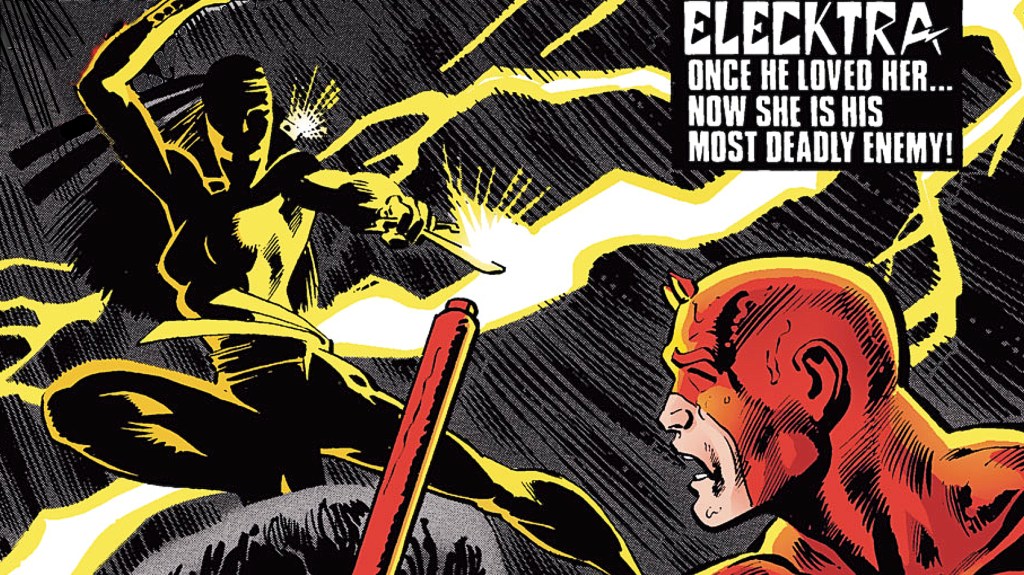

Miller first came to Daredevil as an artist, working initially for Roger McKenzie and then for David Michelinie. Less than a year after his debut on Daredevil, he transitioned into the full-time writer/penciler role with Daredevil (1964) #168. This issue is notable not only because Miller took full creative control of the title but also for introducing Elektra Natchios. Under Miller’s guidance, Elektra would become one of the most iconic characters in the Marvel Comics Universe. Indeed, one of the reasons Miller’s run on Daredevil is considered groundbreaking is how Elektra evolved throughout the series, becoming integral to Miller’s Daredevil mythos.

In addition to Elektra, Miller introduced Daredevil’s mentor Stick and redefined classic Marvel characters like Wilson Fisk’s Kingpin and Bullseye. These additions gave Daredevil a formidable roster of compelling adversaries and allies, all of whom played off Miller’s transformed version of the hero. By adding layers of complexity and vulnerability to Daredevil, Miller made him a far more engaging character than his earlier, blander incarnation.

Outside of Miller’s character-driven changes, perhaps the most obvious shift he brought to Daredevil was the overall vibe. Drawing on the same manga and film noir influences he would later depict with such creative force in The Dark Knight, Miller installed a darker, grittier mood that departed from the traditional, wide-open, and flashy superheroism of comic books like Iron Man or Captain America. Instead, Miller set Daredevil’s world in the back alleys and shadow-filled rooms of New York’s crime-ridden urban jungle, specifically the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood.

Miller Broke the Mold With Daredevil, But Modern Creators Have Made Their Own Molds

One of the most exciting elements of Miller’s run was that he was doing things in comic books that were unheard of at the time. Indeed, mature themes, realism, and complex storytelling were rarely found in mainstream superhero comics in the early 1980s. While these aspects were exceptional then, they have since become the norm. As a result, the elements of Miller’s Daredevil that were once cutting-edge and revolutionary now feel outdated, overly dark, and rather simplistic.

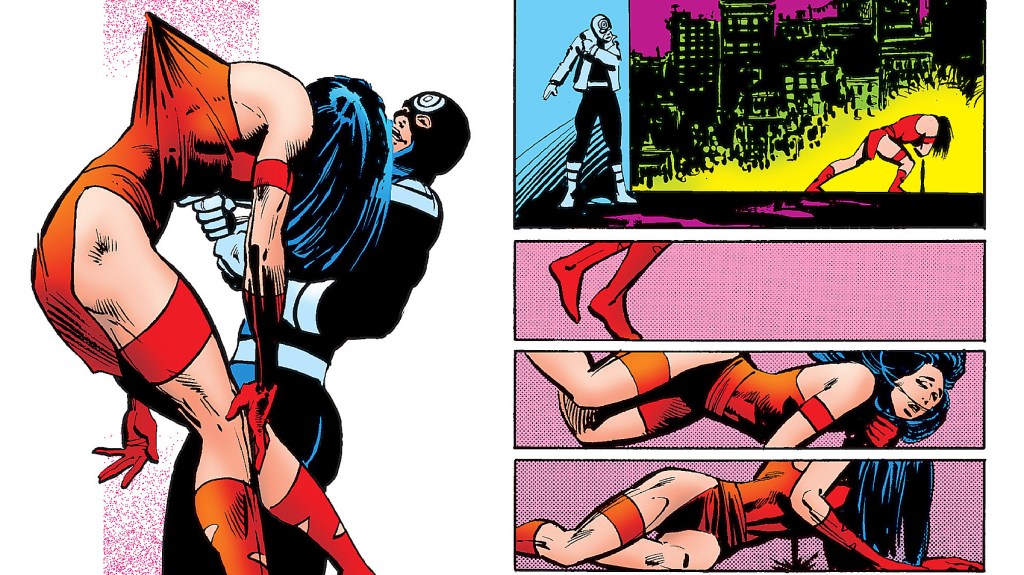

For instance, the death of Elektra in Daredevil (1964) #181 remains one of the most shocking moments in Marvel history. Its “shock value” stems largely from the jaw-dropping surprise of the event itself and the intensity of its execution — it was the comic book equivalent of a jump scare. While this technique still has its place, modern readers tend to seek more than just visceral impact from character deaths. They crave deeper emotional and psychological exploration, particularly the kind of turmoil Daredevil would naturally face if Elektra were killed. Contemporary comics, such as Tom King’s Batman, continue to deliver shocking deaths, but they temper the darkness with complexity and nuance – something that was missing from Miller’s Daredevil.

Miller’s Daredevil is Timeless, but not Untouchable

Miller’s characters and characterizations are another set of issues that, while groundbreaking during their initial publication, now feel flat and dated. In the original run, Miller not only introduced Elektra but also completely redefined classic Marvel characters like Kingpin (Wilson Fisk) and Bullseye, both of whom provided Daredevil with a formidable and compelling cast of threats and opponents. This roster, coupled with Miller’s transformed depiction of Daredevil, added layers of complexity and vulnerability, making him a much more interesting character than his previously bland portrayal.

Nowadays, the only character from the Miller’s run who has truly “aged” well is Daredevil. This is largely thanks to the creative teams that followed Miller, who built upon his foundation to develop an even more complex and nuanced hero. For example, Brian Michael Bendis expanded the exploration of Daredevil’s psyche, while Chip Zdarsky introduced greater spiritual and political depth to Hornhead.

This, however, is not the case for the other main characters from Miller’s Daredevil. For instance, fandom’s early admiration for Elektra has grown more complicated over the years. While she was once praised as a much-needed depiction of a serious, deadly, and professional female superhero, she is now often viewed as an over-sexualized embodiment of classic femme fatale and tragic lover tropes. Notably, some critics have labeled her the epitome of the “fridging” trope — her value defined primarily by how her death advances Daredevil’s emotional development.

In retrospect, Kingpin and Bullseye, though effective in their original roles as the calculating criminal mastermind and the psychotic killer, now seem two-dimensional by modern standards. They lack the psychological depth and tragic nuance that contemporary fans expect — qualities regularly explored in the work of later creators like Ed Brubaker and Brian Michael Bendis.

But these criticisms of Miller’s Daredevil are not meant to suggest it is unworthy. On the contrary, Miller’s Daredevil remains a landmark in modern superhero comics. Rather, the critique reflects how even the most celebrated works can fade and lose some of their luster over time.